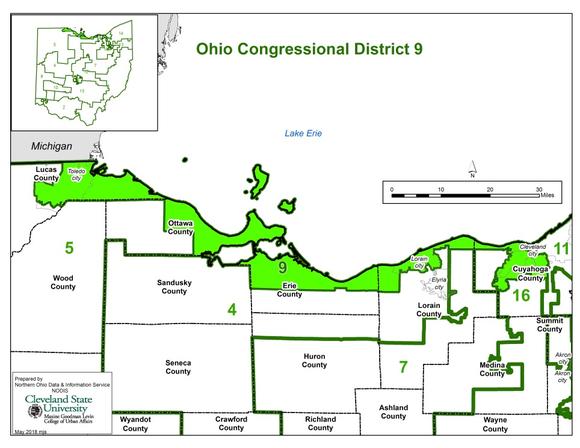

If U.S. Rep. Marcy Kaptur (D) of Ohio wanted to represent her entire district, she would have to cross 101 miles from one end to the other.

Stretching from Lucas County’s Toledo to Cuyahoga County’s Cleveland, the 9th Congressional District, known as the “Snake on the Lake,” is one example of Ohio’s many unusually shaped districts, making Ohio the poster-child of gerrymandered states.

Ohio’s jagged patchwork of districts that cuts through communities is a result of a state-led political activity called “gerrymandering;” a process causing Ohio voters to be inaccurately represented in Congress. Although former attempts for fair representation have failed, two initiatives are gaining bipartisan support and promising to break through Ohio’s slanted political history.

Background

The term gerrymandering dates back to 1812 when the governor of Massachusetts, Elbridge Gerry, discovered that the power of drawing district lines can be used for political advantage or to “stack the deck for your own party,” said state Sen. Frank LaRose, R-Akron.

“Gerry drew a district so egregious that it looked like a salamander,” he said. As a result a newspaper reporter coined the name “gerrymander.”

“2012 was the 200th year of gerrymandering,” said LaRose. “Here we are over 200 years later and it’s only gotten worse.”

The Issue

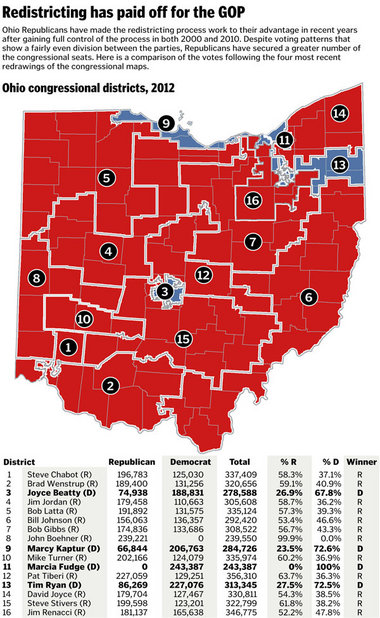

In November 2012, approximately 51 percent of Ohioans voted in favor of President Obama and 52 percent voted in favor of the Republican candidates for Congress.

According to OSU political science professor Richard Gunther, “The bottom line, which you’ll find here, is that Ohio is approximately 50 percent Republican and 50 percent Democrat.”

Although this percentage is about half of the population, Republicans hold 75 percent of Ohio’s seats in the U.S. House of Representatives. Instead of equal representation, there are only four Democrats representing Ohio in the House compared to 12 Republican representatives.

“[Currently] depending upon who you are, either you’re making out like a thief,” Gunther adds, “or you’re being cheated out of your fair share of representation, and that’s not what democracy is about.”

Congressional Redistricting: How it works

Every ten years the states are required to redraw district lines in order to adapt to population shifts; districts are redrawn and reapportioned: each district is made equal in population to all other congressional districts.

How does the apportionment board work?

Who draws state and congressional district lines?

In Ohio two different groups draw district boundaries.

The Ohio Apportionment Board draws the districts for the state House and state Senate and is comprised of the Ohio governor, secretary of state, auditor and one Democratic and one Republican legislator, Ohio State political science professor Richard Gunther said. “So that’s a total of five and all you need is a simple majority in order to ramrod through whatever map you’d like.”

LaRose explained that the boundaries for the U.S. congressional districts are created when the state legislature, the state House and the state Senate, pass a bill with the signature of the governor.

“Either way if you have majority of both chambers and/or the governor, and right now Republicans control all three of them, then you’re in charge of drawing the district lines,” he said.

In theory, La Rose said, districts should represent communities and the interests of their voters. In practice, gerrymandering is the strategic drawing of district lines to maximize the number of one party’s representatives (won by slimly held majorities) and to cram as many minority party votes as possible into as few of districts as possible, in order to gain the maximum potential seats. The formation of slim majorities and supermajorities are often given the slang ‘packing and cracking’ the districts, groupings used to distort otherwise proportional representation.

Kaptur’s 9th congressional district is an example of a supermajority, where the democratic votes of northern Ohio and its major urban centers (Toledo, Sandusky, Cleveland) are packed into one district. In 2012 she beat her opponent, the Republican candidate Samuel Wurzelbacher, by over three times his number of votes (73 percent to 23 percent) according to NBC News. (Her 73 percent to his 23 percent or 206,763 total votes to 66,844 total votes).

LaRose, a member of the majority party who also represents a gerrymandered Ohio 27th Senate District, explained this lack of competitiveness:

“Most of my colleagues who are good people with good intentions, but they live in and represent districts where the only challenge to their election is in the primary election, not the general election.”

According to Gunther, the way the boundaries are currently drawn, a party’s supermajority guarantees that some politicians, like Kaptur, “have jobs for life.”

Currently the majority party in Ohio is the Republican Party; however, in the past Democrats have utilized these same strategies to obtain the majority of possible seats in the House.

Over two centuries the Gerrymandering process has evolved, aided by new technologies.

Advances in computer mapping such as Geographic Information Systems (GIS) technology provides details down to an individual household, with lines drawn to cut across streets and between houses.

La Rose added, “We know that Republicans live in this house and we know that Democrats live in this house and the folks that draw the lines can draw it down to the granular detail.”

Gunther summarized, “This is the local outcome of allowing politicians to draw their own district lines. No other democracy in the world allows that. None.”

Although groups have proposed multiple redistricting reforms, past attempts have been unsuccessful. For over almost 40 years political leaders have criticized Ohio’s gerrymandered districts and in the last nine years there were three major attempts to reform congressional redistricting in Ohio.

Although past attempts have failed, today there are two different redistricting reform initiatives in the state legislature and Ohio Constitutional Modernization Commission.

“Because both parties are now looking to ten years down the road and they don’t know who’s going to be controlling the redistricting process and they want to try to make it a little bit more fair” Gunther said. “Although you may be in control of the redistricting process now, there no guarantee that you’re going to control the process the next time around.”

Two Reform Efforts

A new reform proposal, Senate Joint Resolution 1 has recently passed out of committee and is pending approval in the Senate. This plan would create somewhat different reapportionment board by adding one additional Democrat and one additional Republican from the legislature. In order to pass future redistricting plans this resolution would require one member of the minority party to vote in favor of the plans, mandating bipartisan support.

Sens. Tom Sawyer (D), Frank LaRose (R), Nina Turner (D), and Keith Faber (R) sponsor Senate Joint Resolution 1. The resolution was favorably reported out of State Government Oversight Committee and is awaiting consideration by the entire Senate chamber, according to Matt McDonnell, the legislative aide to Sen. Frank LaRose.

Simultaneously, the Ohio Constitutional Modernization Commission will propose reforms. LaRose said the commission is comprised of “real luminaries” including a former governor and former office holders from both parties. Although the commission’s ideas regarding reform will be influential, LaRose said the initiative still depends on the votes of partisan legislators and has its drawbacks:

“But what they recommend is still just that, a recommendation to us in the general assembly.”

LaRose and Gunther both said they anticipate that the commission’s recommendation will be similar to Senate Joint Resolution 1, expanding the redistricting board by adding one Republican and one Democrat.

Do young Ohioans care?

“It makes you wonder, are we really electing our representatives, or are they choosing us?”

Vincent Hayden

Students across campus shared their opinion of this reform effort and Ohio’s current political state.

“Gerrymandering is a disservice to democracy,” said Will Crawford, a recent graduate in public affairs and former White House intern in the Office of Scheduling and Advance, adding it is unfortunate there has not yet been a solution; “both parties are guilty of manipulating the boundaries when in power.”

Grant Ames, a former OSU political science student, said, “We need reform to improve Ohio’s representation. In republics, political representation equals freedom. And with Ohio’s unrepresentative government Ohioans’ freedoms are at risk.”

Members of College Republicans and College Democrats also voiced their opinions about Ohio’s current redistricting process.

Miranda Onnen, the communications director for the College Republicans and a fourth-year in economics and political science, said in an email that gerrymandering is “detrimental to the political process. It creates more partisanship and gridlock, which in turn limits the government’s ability to get things done.”

President of OSU College Democrats and fourth-year in political science, Vincent Hayden, said that because of gerrymandering, Ohio college student do not think their voices matter.

“The way our districts are drawn, they’re right” he said. “It makes you wonder, are we really electing our representatives, or are they choosing us?

The future:

The state is taking steps toward reform and the commission should release its recommendations within the next few months. Following this recommendation it would move to the legislature, which then has to approve a constitutional amendment on the ballot and then the voters would have to approve that constitutional change, Gunther said.

“So it’s a very long process, but one thing is but one thing is clear, the current process does not serve the interests of Ohio voters.”

First written: 4.15.14